Wireless spectrum is a natural resource. Who says it's owned by the FCC?

A conversation with Darrah Blackwater, an attorney, artist, and leading advocate for the right of Native nations to control the waves in their airspace

Darrah Blackwater is an attorney and artist from Farmington, New Mexico and a citizen of the Navajo Nation. Her research into the Indigenous digital divide led her to become a powerful advocate for spectrum sovereignty, the idea that the wireless spectrum on and above Native land should be owned and governed by the Native people on that land.

I first met Darrah at a human rights conference in San Jose, Costa Rica. Her talk did what all the best do—it pushed at the edges of imagination. I had never thought of the electromagnetic spectrum as a natural resource akin to water, earth, and oil, but the radio waves moving through the air were there long before they became profitable. Sovereignty over spectrum is entwined with #LandBack and other fights for Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination.

On top of her legal work and art practice, Darrah has been involved in network builds across tribal nations including in Waimānalo, Hawaii, where wireless signals bounce off banana leaves. I spoke with Darrah over Zoom, and our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Anna Bonesteel: Could you give an overview of what wireless spectrum is, how we move through it, and how it's regulated in the US?

Darrah Blackwater: Wireless spectrum, or electromagnetic spectrum, is essentially radio waves. It’s the spectrum of frequencies we use for telecommunications and more: everything from X-rays, microwaves, and garage door openers, all the way to cell phone service, wireless internet, and radio. All of these things use electromagnetic spectrum, or spectrum for short.

Spectrum is a natural resource. It's not created by any person or any company—it occurs naturally on the land. It's created by the interaction of stars, sun, earth, and rocks, and the way that naturally occurring frequencies interact with the earth and air around us. We've learned how to send information over these frequencies, and we’re getting better at it. That means that spectrum is more useful to us for things like video calls, or TikTok, or anything that’s data heavy.

Because spectrum is now more valuable to us, it’s also more valuable in a financial sense. People are willing to pay to have control over spectrum. That shakes out in government regulation like this: the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) sells licenses to use spectrum at a certain time, in a certain space, on a certain frequency. The FCC holds auctions where people can purchase licenses to broadcast over a certain frequency, and different frequencies are good for different services. So, you could buy a license over... Where are you right now, Anna?

AB: I'm in Montréal, actually.

DB: Okay, so you wouldn't be buying it from the FCC, you would be buying it from the CRTC in Canada, but I'm in Washington DC right now. So, if I was a big telecom company with deep pockets, I could bid on a radio broadcast license for the next 10 years in Washington DC. I would bid against every other company that wants those rights, and whoever offers the most money for it would win the license.

The FCC has made over $230 billion from spectrum license auctions since they started doing auctions in 1994. So, it's very expensive to get spectrum licenses, and it’s very lucrative for the FCC and the government.

These licenses are being sold without respect to tribal boundaries. Normally on Indian or reservation land, a tribe has jurisdiction over everything within their boundaries. That could be the coal, oil, or gas in the ground, the trees that grow on the ground, or the water that flows through the land. My argument is that because spectrum is a natural resource, tribes should be recognized as the ones who get to financially benefit from the spectrum on their land. Ideally, they would be able to manage and consent to any sales or licensure of the spectrum within their boundaries.

AB: How did you first become interested in spectrum sovereignty?

DB: I was an intern with the Udall Center in 2018, back when I was in law school, and I worked as an intern for the Department of Interior for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. That summer, they told me to go figure out what was causing the digital divide in Indian country, because that's what everyone was talking about...

AB: Yeah, so send an intern to go do it.

DB: Yeah. I was the youngest one in the office, and they were like, “We don't understand computer technology, you go figure it out.”

I was going to meetings all over the Hill to learn about the digital divide in Indigenous communities. I didn't know anything about spectrum, but I kept hearing that word come up. As I learned more about it, I recognized that it was a natural resource. And as soon as I realized it was a natural resource, I knew that what was happening with spectrum is what has happened with pretty much every natural resource since the beginning of colonization on this continent, which is that it was being taken out from under tribes without consent or compensation.

AB: The land is stolen, then the spectrum is stolen… Your conference presentation discussed the difference between ancestral lands and reservation lands. It sounds like there could be a lot of stolen ancestral land in play, too.

DB: In general, tribes that have little or no land are at a huge disadvantage, because if you don't have recognized jurisdiction over land or resources, you’re way behind in potential economic development. The same goes for spectrum. If you don't have land recognized, it's hard to have spectrum recognized. I'm really interested in exploring what it would look like to recognize a tribe's right to spectrum within their federally recognized boundaries, and also give tribes access to spectrum in a way that serves their citizens no matter where they are.

In my utopian dream of spectrum sovereignty for all Indigenous people on this land, we aren’t bound by the recognition granted by Federal Indian law. It doesn't live in that box. Only part of it lives in that box, and there's a much broader picture.

AB: As it stands, how does lack of tribal sovereignty over spectrum impact tribes’ connection to Internet and other services?

DB: The federal government refusing to recognize tribal sovereignty over spectrum creates more barriers for tribes that are trying to connect. There are 574 federally recognized tribes within the United States, and each one has to figure out where to start their connection projects based on the priorities of their communities. Some tribes might be focused on public safety, especially if they're on a highway where a lot of women and other people go missing or get murdered. Maybe another tribe’s top priority is gaming, because they're in an urban area and gaming’s where they get a lot of their tribal revenue to run their social services; they might want to connect their casinos before anything else. Maybe they're focused on schools, and they have a robust education system that they are focused on connecting first and foremost.

Every tribe has a different answer to what’s most important to them, and if they can't access or afford spectrum licenses, it's going to take longer to implement their plans, there’s going to be a lot of red tape, and it’s going to be very expensive. Wireless builds on tribal lands would be much easier, cheaper, and more practical if the United States recognized tribal sovereignty over spectrum.

AB: What’s the current state of the field, in the US and internationally? Are Indigenous groups beginning to achieve sovereignty over the spectrum in their airspace?

DB: Yes, this movement is global. Recently, a council of chiefs in Canada passed a resolution calling for spectrum sovereignty from the government of Canada.

In New Zealand, the Crown signed a memorandum of understanding with the Māori Interim Spectrum Commission. This agreement allows the Māori Interim Spectrum Commission to hold 20% of national spectrum moving forward, on behalf of Māori people. The agreement hinges on cases from the Waitangi Tribunal that characterize spectrum as Taonga, which means “something treasured.” Because spectrum falls under that category, the Māori can claim rights to spectrum.

It’s complicated because the Waitangi Tribunal's decisions aren't binding on the Crown. In the memorandum of understanding the Crown basically said, “We're doing this out of the kindness of our heart. We know we're not bound by this court case.” So, there's a lot of sidestepping, but it's a step in the right direction.

Mexico has made some huge steps in recognizing that Indigenous people have rights to spectrum. And when I was speaking at the conference you attended, some people from Guatemala and Columbia were telling me that they've also made progress in their countries.

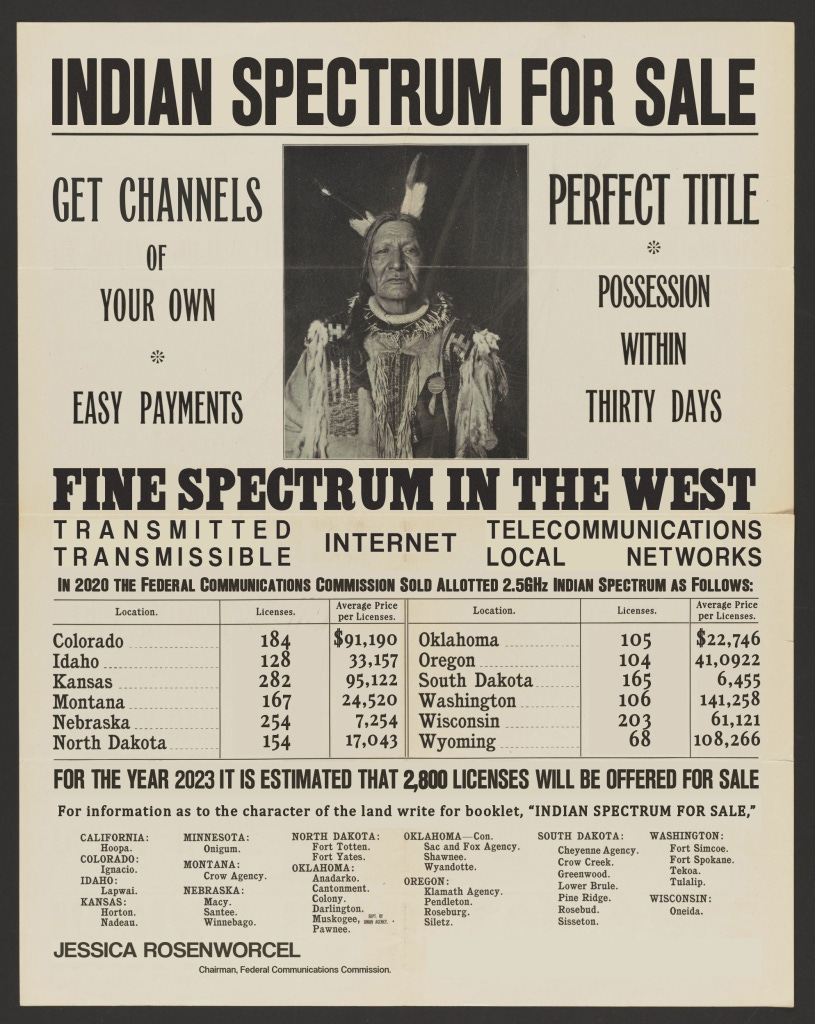

In the US, it’s less substantial. In 2020, there was something called a rural tribal priority window. This was a period during which the FCC was allowing tribes to apply for a 2.5 gigahertz spectrum license, which is good spectrum for rural areas. It was only for “rural” tribes, which is a very arbitrary distinction—we've never seen a legal distinction like that in Federal Indian law. Ajit Pai was the chairman of the FCC at the time, and he just made it up, you know? It was a step in the right direction, but also, in my mind, a slap in the face—making tribes fill out an application to possibly get a crumb of the cookie that the FCC took from tribal lands.

AB: In the Navajo/Diné tradition, how is airspace conceptualized? How is thinking about it different from the colonial mindset?

DB: Many Indigenous peoples have deities who are representative of spectrum, through imagery of lightning, and sunlight, and energy coming off of rocks. These things are very much sacred. They’re part of many ceremonies and they’re part of the Indigenous worldview.

In Diné culture we have Jóhonaaʼéí, who is Sunbearer. Sunbearer is the god who carries the sun across the sky every day. We have lightning deities, who are also very powerful. So there's the imagery and the deities, but I think there's also a deeper understanding of the way that energy moves through space, and the ways that it can be utilized by us. There’s an additional concept of Hózhó, which means balance. Hózhó connects to how our bodies synchronize with the sun moving across the sky each day. It's a sacred thing that we very much take for granted.

In Diné culture, we’re taught to greet the sun because we believe the deities, our creator, are most present with us as the sun is coming up. The Navajo way to wake up every morning is to run east, greet the sun, and then pat the first rays of light onto your skin. That very first time that you're experiencing spectrum is a sacred moment that will give you the strength to take you through the day.

I think the very presence of spectrum in the Diné, the Navajo worldview is extremely powerful. Then you add in all the ways that we're interacting with the spectrum—telecommunications, using our phones, video chatting—these are powerful experiences that have the potential to either go really well or go really poorly. When you interact with spectrum through the first rays of sunlight coming over the horizon, it brings a sense of respect and importance to every interaction that follows.

AB: The sensation of light and of vision leads me to art making. I was wondering if you could speak a little to your art practice, how it intersects with your legal work, and then if there are any people you think are making great artwork right now that folks should check out.

DB: Being an artist and an attorney is something I'm learning how to do, because I really need both parts of me to feel balanced. I can tell when being an attorney starts taking up too much space in my mind, because all I want to do is art sometimes! I just got a grant through the Indian Collective, and I'm excited to dive back into the creative space and make art that's influenced by what I've experienced as an attorney.

Indigenous history and policy, a lot of it is so heavy. For some people, the only way to express the heaviness and the grief of it is through something artistic, because the laws fall short. Thinking about boarding schools, for instance—you can read something that almost sterilizes it, for lack of a better word. But then to see a Kent Monkman painting of a little girl in a boarding school looking at a bird on a windowsill, and you just know that she's wishing she could be that bird and fly away from that school and never return... It's just such a different experience.

We have to understand the laws and policies that led to that little girl standing by that windowsill, but then to see it and experience what she's feeling in those moments of being so alone and so fearful, out of bed in that boarding school—you need both.

I'm in DC right now, and it's very inspiring to see how people are also trying to strike that balance. There's a lot of amazing art in the museums, and then a lot of brilliant people, a lot of Native attorneys out here who are really amazing as well. I just went to the Renwick Gallery, right by the White House. There's a show with multiple Native artists. Erica Lord is doing a really amazing project on DNA mapping using beadwork, and then there’s Geo Neptune, a Passamaquoddy basket maker who also has these really amazing works. That was really inspiring to see today.

I'm trying to figure out how to channel these ideas, thoughts, and experiences I've had into art, in a way that's not too much information, but is also very impactful. That's my journey as both an artist and a lawyer, and I try to do it well.

Incredible conversation